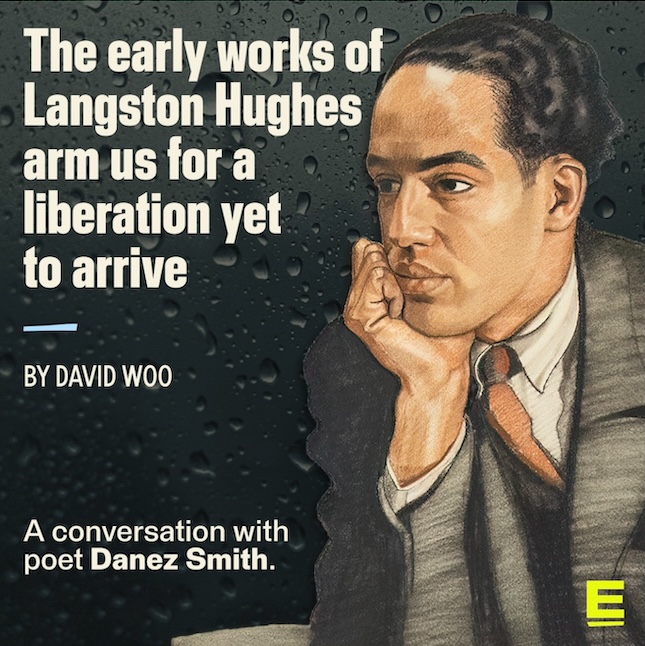

From my interview with Danez Smith about their curation of the early works of Langston Hughes for the anthology Blues in Stereo:

David Woo: Your poetry books display a complex pride, urgency, and despair in your experience of race. In Bluff, you say, “i want to be over with race / but race ain’t over me.” And in your first book, “[insert] boy,” you wrote, “If race is over, did we lose?” What is striking about Blues in Stereo is how healing Hughes’ love of Black people feels to those of us who feel despair over 21st-century oppressions. Can you talk about Hughes’ vision of race and how it relates to your experience today?

Danex Smith: For me, Hughes’ vision of race, country, and community is not one without despair, but despair never swallows what is joyful and possible, and in turn that joy and beauty never erase what is ugly and true. I wanted to center Blues in Stereo on how much Hughes loved Black people. When I read his work, I feel him wanting me to feel beautiful, strong, redeemed, believed, and safe — safe enough to admit I’m weary and worried, too. I feel that same tie in my own work. What is raging, pissed, despairing, exhausted, grieving, or vengeful all leads back to love, how to love the race; the people. When Black adults want to teach Black kids how and why to love themselves, they will reach for art, and when they reach for poems, it is very possible you might get a Hughes poem when you are being taught to see and love Blackness. I think of what the great Evie Shockley (who I hope is being read by Black kids learning to love themselves 100 years from now) said in her “ode to my blackness:”

you are my shelter from the storm

and the storm

my anchor

and the troubled sea

And I think that balance is something all Black poets who write about Blackness contend with; how to tell of the anchor, how to tell also of the troubled sea, how to survive the storm and be the storm. Hughes knew how to do it all. I know Hughes believed in revolution and, as healing and beautiful as he wanted his poems to be for us, he also wanted to arm us with the wisdom, hope, and power to fightfor a liberation yet to arrive.